- Essentials

- Getting Started

- Agent

- API

- APM Tracing

- Containers

- Dashboards

- Database Monitoring

- Datadog

- Datadog Site

- DevSecOps

- Incident Management

- Integrations

- Internal Developer Portal

- Logs

- Monitors

- Notebooks

- OpenTelemetry

- Profiler

- Search

- Session Replay

- Security

- Serverless for AWS Lambda

- Software Delivery

- Synthetic Monitoring and Testing

- Tags

- Workflow Automation

- Learning Center

- Support

- Glossary

- Standard Attributes

- Guides

- Agent

- Integrations

- Developers

- Authorization

- DogStatsD

- Custom Checks

- Integrations

- Build an Integration with Datadog

- Create an Agent-based Integration

- Create an API-based Integration

- Create a Log Pipeline

- Integration Assets Reference

- Build a Marketplace Offering

- Create an Integration Dashboard

- Create a Monitor Template

- Create a Cloud SIEM Detection Rule

- Install Agent Integration Developer Tool

- Service Checks

- IDE Plugins

- Community

- Guides

- OpenTelemetry

- Administrator's Guide

- API

- Partners

- Datadog Mobile App

- DDSQL Reference

- CoScreen

- CoTerm

- Remote Configuration

- Cloudcraft (Standalone)

- In The App

- Dashboards

- Notebooks

- DDSQL Editor

- Reference Tables

- Sheets

- Monitors and Alerting

- Service Level Objectives

- Metrics

- Watchdog

- Bits AI

- Internal Developer Portal

- Error Tracking

- Change Tracking

- Event Management

- Incident Response

- Actions & Remediations

- Infrastructure

- Cloudcraft

- Resource Catalog

- Universal Service Monitoring

- End User Device Monitoring

- Hosts

- Containers

- Processes

- Serverless

- Network Monitoring

- Storage Management

- Cloud Cost

- Application Performance

- APM

- Continuous Profiler

- Database Monitoring

- Agent Integration Overhead

- Setup Architectures

- Setting Up Postgres

- Setting Up MySQL

- Setting Up SQL Server

- Setting Up Oracle

- Setting Up Amazon DocumentDB

- Setting Up MongoDB

- Connecting DBM and Traces

- Data Collected

- Exploring Database Hosts

- Exploring Query Metrics

- Exploring Query Samples

- Exploring Database Schemas

- Exploring Recommendations

- Troubleshooting

- Guides

- Data Streams Monitoring

- Data Observability

- Digital Experience

- Real User Monitoring

- Synthetic Testing and Monitoring

- Continuous Testing

- Product Analytics

- Session Replay

- Software Delivery

- CI Visibility

- CD Visibility

- Deployment Gates

- Test Optimization

- Code Coverage

- PR Gates

- DORA Metrics

- Feature Flags

- Security

- Security Overview

- Cloud SIEM

- Code Security

- Cloud Security

- App and API Protection

- AI Guard

- Workload Protection

- Sensitive Data Scanner

- AI Observability

- Log Management

- Observability Pipelines

- Configuration

- Sources

- Processors

- Destinations

- Packs

- Akamai CDN

- Amazon CloudFront

- Amazon VPC Flow Logs

- AWS Application Load Balancer Logs

- AWS CloudTrail

- AWS Elastic Load Balancer Logs

- AWS Network Load Balancer Logs

- Cisco ASA

- Cloudflare

- F5

- Fastly

- Fortinet Firewall

- HAProxy Ingress

- Istio Proxy

- Juniper SRX Firewall Traffic Logs

- Netskope

- NGINX

- Okta

- Palo Alto Firewall

- Windows XML

- ZScaler ZIA DNS

- Zscaler ZIA Firewall

- Zscaler ZIA Tunnel

- Zscaler ZIA Web Logs

- Search Syntax

- Scaling and Performance

- Monitoring and Troubleshooting

- Guides and Resources

- Log Management

- CloudPrem

- Administration

How to monitor non-static thresholds

Overview

A typical metric monitor triggers an alert if a single metric goes above a specific threshold number. For example, you could set an alert to trigger if your disk usage goes above 80%. This approach is efficient for many use cases, but what happens when the threshold is a variable rather than an absolute number?

Watchdog powered monitors (namely anomaly and outlier) are particularly useful when there isn’t an explicit definition of your metric being off-track. However, when possible, you should use regular monitors with tailored alert conditions to maximize precision and minimize time-to-alert for your specific use case.

This guide covers common use cases for alerting on non-static thresholds:

- Alert on a metric that goes off track outside of seasonal variations

- Alert based on the value of another reference metric

Seasonal threshold

Context

You are the team lead in charge of an e-commerce website. You want to:

- receive alerts on unexpectedly low traffic on your home page

- capture more localized incidents like the ones affecting public internet providers

- cover for unknown failure scenarios

Your website’s traffic varies from night to day, and from weekday to weekend. There is no absolute number to quantify what “unexpectedly low” means. However, the traffic follows a predictable pattern where you can consider a 10% difference as a reliable indicator of an issue, such as a localized incident affecting public internet providers.

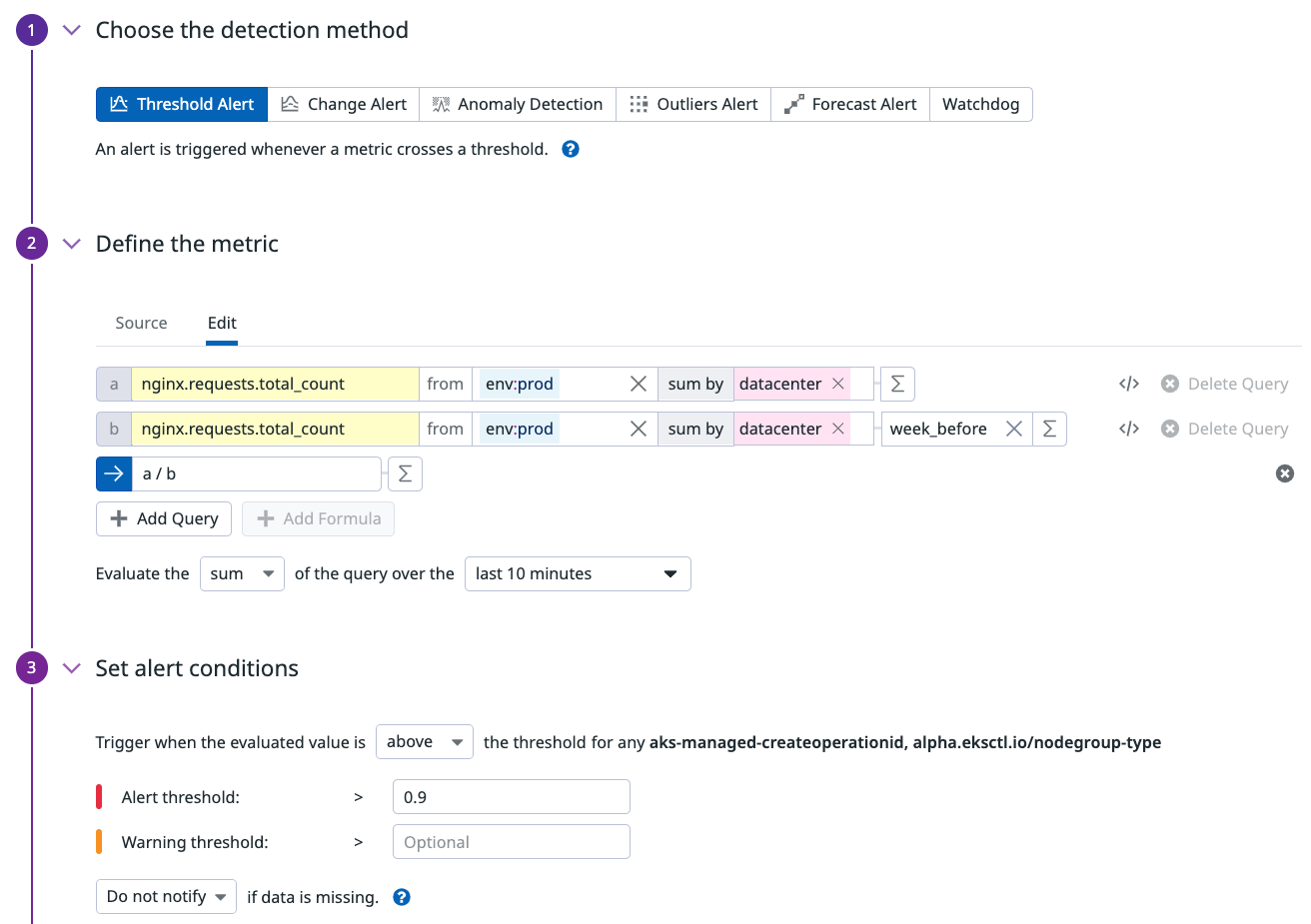

Monitor

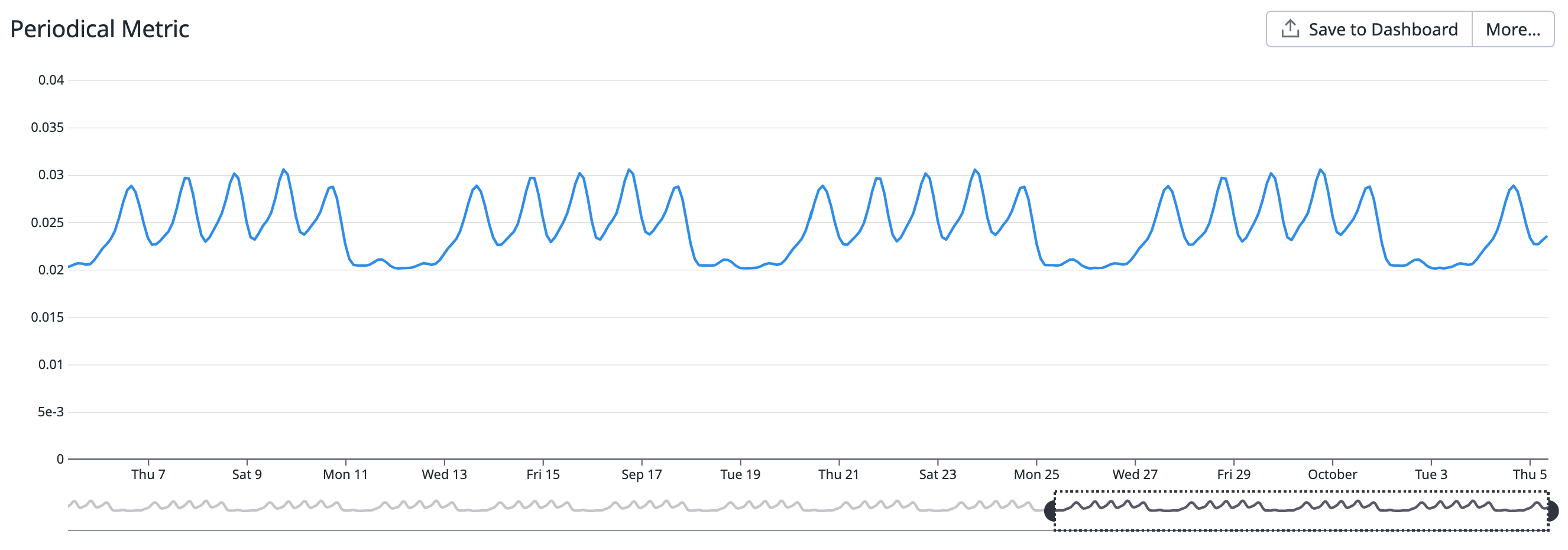

Your team measures the number of connections on your NGINX web server using the nginx.requests.total_count metric.

The request consists of 3 parts:

- A query to get the current number of requests.

- A query to get the number of requests at the same time a week before.

- “Formula” queries that calculate the ratio between the first two queries.

Then, decide on the time aggregation:

- You choose the timeframe. The bigger the timeframe, the more data it evaluates to detect an anomaly. Larger timeframes can also result in more monitor alerts, so start with 1 hour, then adjust to your needs.

- You choose the aggregation. Since it’s a count metric performing a ratio,

average(orsum) is a natural choice.

The threshold displayed in the screenshot below has been configured to 0.9 to allow for a 10% difference between the value of the first query (current) and the second query (week before).

{

"name": "[Seasonal threshold] Amount of connection",

"type": "query alert",

"query": "sum(last_10m):sum:nginx.requests.total_count{env:prod} by {datacenter} / week_before(sum:nginx.requests.total_count{env:prod} by {datacenter}) <= 0.9",

"message": "The amount of connection is lower than yesterday by {{value}} !",

"tags": [],

"options": {

"thresholds": {

"critical": 0.9

},

"notify_audit": false,

"require_full_window": false,

"notify_no_data": false,

"renotify_interval": 0,

"include_tags": true,

"new_group_delay": 60,

"silenced": {}

},

"priority": null,

"restricted_roles": null

}

Reference threshold

Context

You are the QA team lead, in charge of the checkout process of your e-commerce website. You want to ensure that your customers have a good experience and can purchase your products without any issues. One indicator of that is the error rate.

The traffic is not the same throughout the day, so 50 errors/minute on a Friday evening is less worrying than 50 errors/minute on a Sunday morning. Monitoring an error rate rather than the errors themselves gives you a reliable view of what healthy and unhealthy metrics look like.

Get alerted when the error rate is high, but also when the volume of hits is significant enough.

Monitor

Create 3 monitors in total:

- Metric monitor to alert on total number of hits.

- Metric monitor to calculate the error rate.

- Composite monitor that triggers an alert if the first two monitors are in an ALERT state.

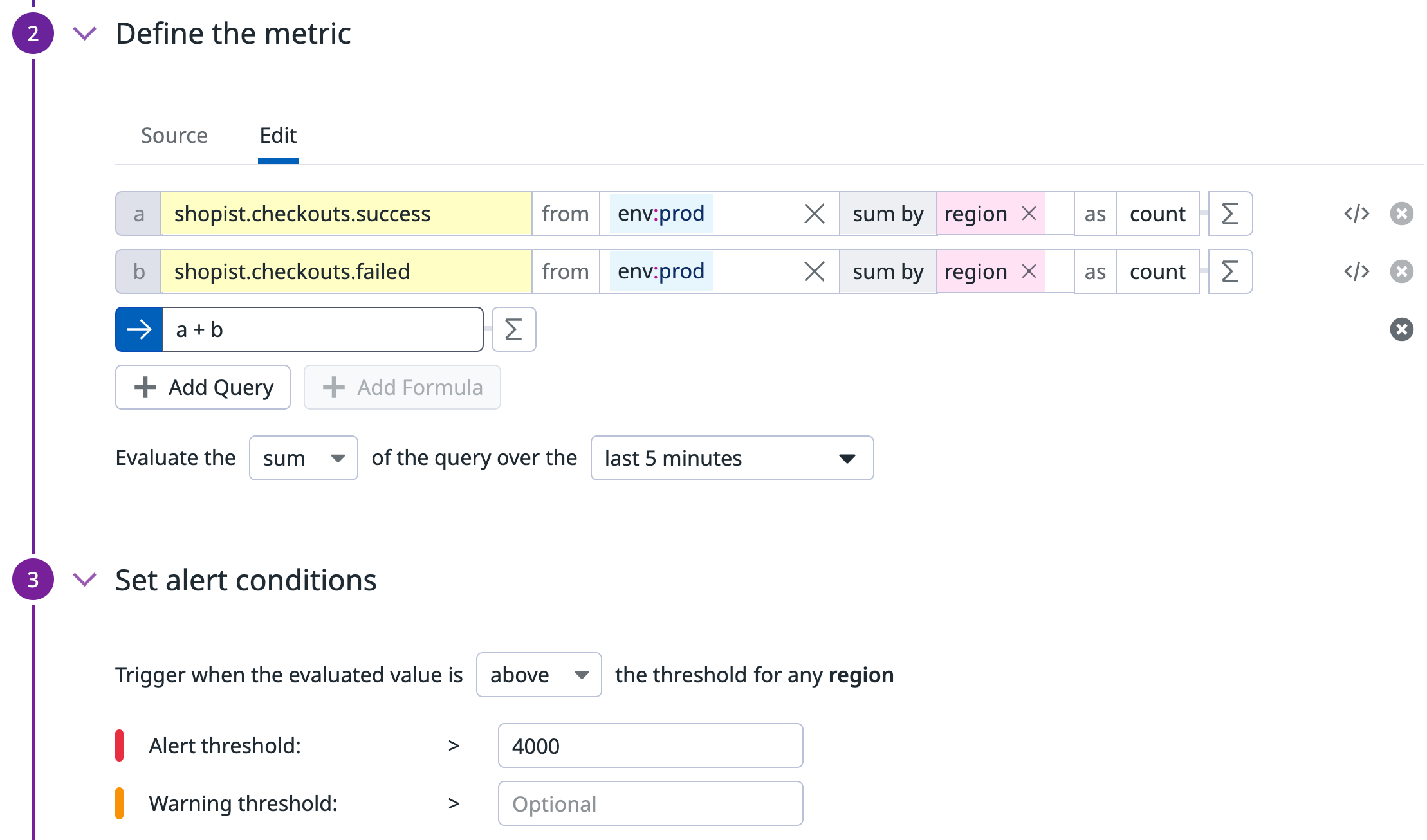

Metric monitor to alert on the total number of hits

The first monitor tracks the total number of hits, both successes and failures. This monitor determines whether the error rate should trigger an alert.

{

"name": "Number of hits",

"type": "query alert",

"query": "sum(last_5m):sum:shopist.checkouts.failed{env:prod} by {region}.as_count() + sum:shopist.checkouts.success{env:prod} by {region}.as_count() > 4000",

"message": "There has been more than 4000 hits for this region !",

"tags": [],

"options": {

"thresholds": {

"critical": 1000

},

"notify_audit": false,

"require_full_window": false,

"notify_no_data": false,

"renotify_interval": 0,

"include_tags": true,

"new_group_delay": 60

}

}

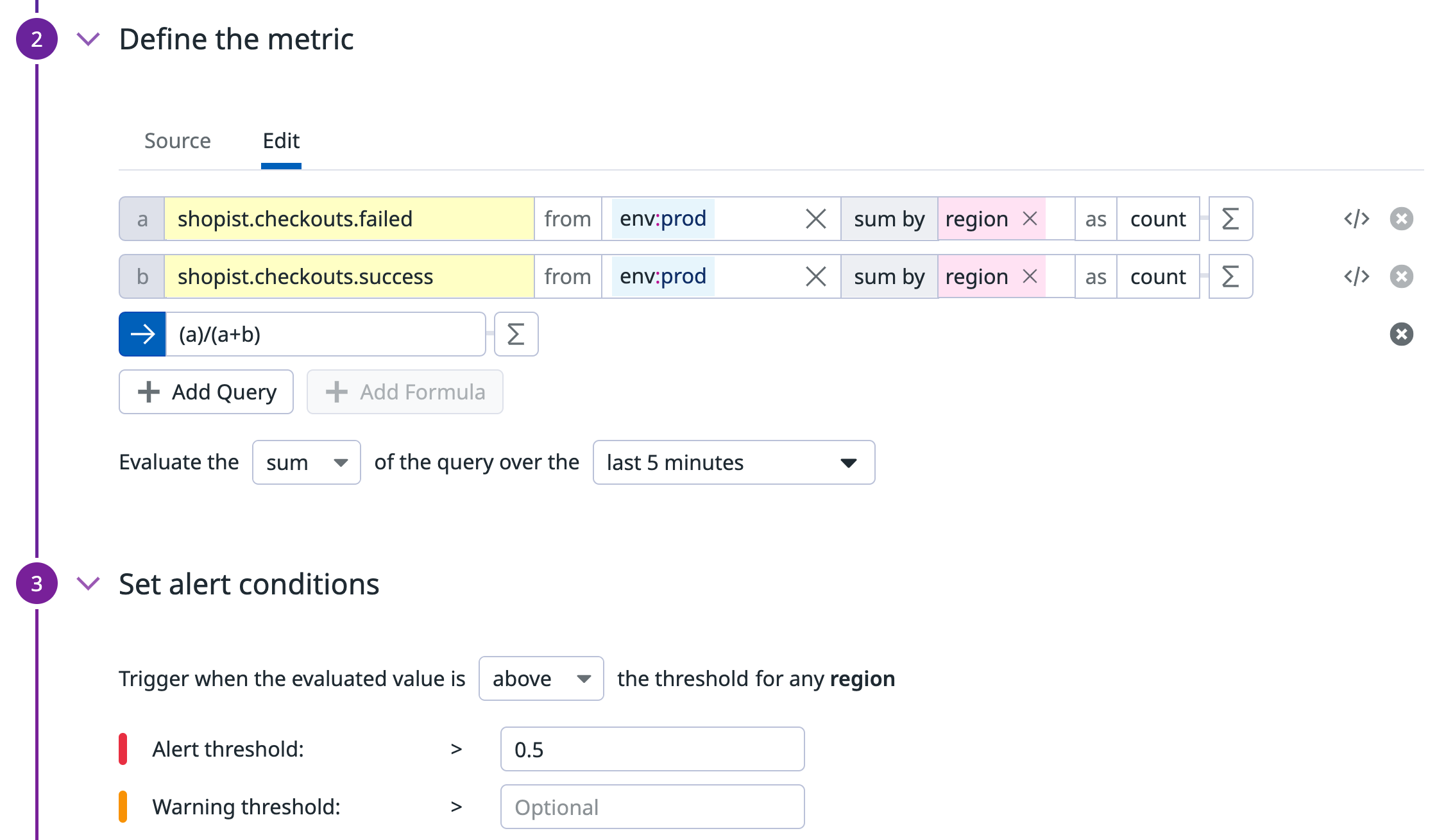

Metric monitor to calculate the error rate

The second monitor calculates the error rate. Create a query on the number of errors divided by the total number of hits to get the error rate a / a+b:

{

"name": "Error Rate",

"type": "query alert",

"query": "sum(last_5m):sum:shopist.checkouts.failed{env:prod} by {region}.as_count() / (sum:shopist.checkouts.failed{env:prod} by {region}.as_count() + sum:shopist.checkouts.success{env:prod} by {region}.as_count()) > 0.5",

"message": "The error rate is currently {{value}} ! Be careful !",

"tags": [],

"options": {

"thresholds": {

"critical": 0.5

},

"notify_audit": false,

"require_full_window": false,

"notify_no_data": false,

"renotify_interval": 0,

"include_tags": true,

"new_group_delay": 60

}

}

Composite monitor

The last monitor is a Composite monitor, which sends an alert only if the two preceding monitors are also both in an ALERT state.

Further reading

Additional helpful documentation, links, and articles: